If your AI product is going head to head with an incumbent, their distribution advantage will probably kill your startup…unless you fight back with a different game.

It is Summer 2023, and each day brings a new AI product demo that goes completely viral on Twitter X or TikTok. Countless people are blown away by the product’s magic-like qualities, powered by GPT4, Stable Diffusion, or some other new language, video, or image model. And while it’s an incredibly exciting time to be building or investing in AI, it’s also a fiercely competitive one as well, especially for teams building in the application layer – the part of the technology stack that delivers real world products to end users interacting directly with software.

The competition is being fueled by what’s at stake: participation in a generational platform shift in which the capabilities (and the potential value) of the tools we use are reaching new heights, all because of AI. We haven’t witnessed a shift of this magnitude since the advent of cloud computing, the mobile revolution, or even the internet. In other words: the stakes are high.

But it also has just as much to do with the fact that building and launching new AI products is arguably easier than ever before, democratized by more accessible coding education, powerful IDEs (aka integrated development environments, which help engineers be more efficient when coding, even aiding them via AI through offerings like GitHub’s Copilot), and the AI itself: companies like OpenAI and Stability, to their credit, have made it really easy for startups to make products using their game-changing tech.

AI is a Commodity

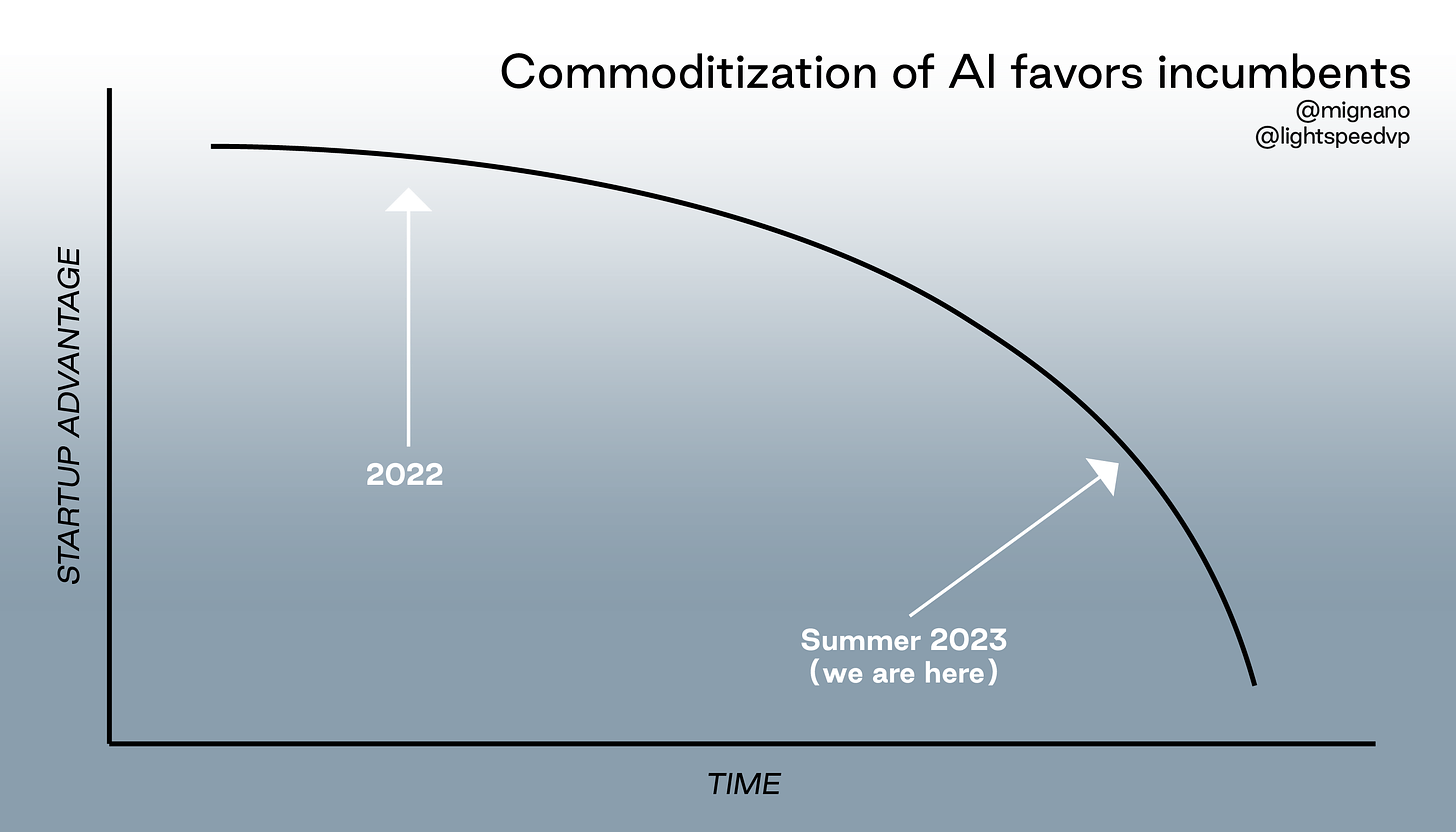

The combination of the high stakes, the excitement, and the accessibility of the technology means that there are a lot of new startups out there building AI products. Seemingly every startup today can (and is!) incorporating AI into their products. But it’s not just the startups…bigger, more established players are also incorporating AI, too. And they’re moving really fast. As a result, AI has quickly become so ubiquitous, that it’s fair to say that it has become commoditized.

Historically, when new technologies have become commoditized, they have gone from being early differentiators for new entrants to becoming table stakes, and a requirement for most products and services to remain competitive. Take mobile apps as one example; shortly after the App Store launched, a handful of exciting and super innovative companies took the plunge and launched apps quickly and well before others. Some of these teams were rewarded handsomely; Instagram, WhatsApp, Uber, and others became big winners of the race to innovate on mobile before others did.

But as smartphone application development became cheaper, and the distribution for mobile became more ubiquitous (in the form of smartphone adoption), it was no longer a differentiator; it was a commodity. And not just for startups, but for incumbents, too.

Speed Matters, But Distribution Matters Most

Like startups, incumbents also want to win platform shifts, but in the early days, the advantage sits squarely on the side of the startups. Startups can see opportunities and act on them swiftly, like in the case of the examples of above. They get products out into the world fast, blitzscale, and win markets.

But as time goes on, the incumbents mobilize. While they may not ship as quickly as the startups, they can move with heft and might, deploying dozens, hundreds, or even thousands of engineers towards a common goal, often on a collision course with an entire category of startups. When this happens, incumbents hold a very valuable advantage, one that’s arguably much more valuable than the size of their teams or the quantum of their investments. That advantage is distribution.

While startups search to find an audience for their new products, incumbents have already found one. While startups iteratively progress to earn the right to spend precious capital on marketing, incumbents already have entire marketing departments. And while startups fight and claw to unearth new hidden promotional channels, incumbents distribute within products already adopted by millions.

All of this is to say that if a new startup is building an AI product that is likely to be offered by an incumbent, then the startup will inevitably face a very steep, uphill battle. After all, the incumbent can offer and aggressively market the same commoditized AI technology to an existing user base of highly qualified customers.

Just take a look at what Adobe is doing with Firefly, as one example. Earlier this year, a handful of super innovative startups were dazzling the world using open source libraries like Stable Diffusion to offer mind-blowing, AI-powered image generation tools. But in recent months, Adobe has moved decisively to offer similar capabilities directly inside of Adobe Photoshop, a product with vast distribution power and an ability to meet millions of creatives where they’re already doing work. And as I learned in a recent conversation with Adobe’s Chief Strategy Officer, Scott Belsky, the company has no plans to take their foot off the gas anytime soon.

How to Play a Different Game

Does this mean all hope is lost for startups? Of course not; after all, this same dynamic has played out repeatedly throughout history, and countless legendary startups have emerged, succeeded, and gone on to become generational companies. So then, what can AI-focused startups do? How can they gain an advantage for AI products in the application layer that are inevitably destined to go head to head with incumbents? Below are 3 examples of strategic tactics startups can take to fend off bigger companies’ home field advantage.

1. Unique Formats

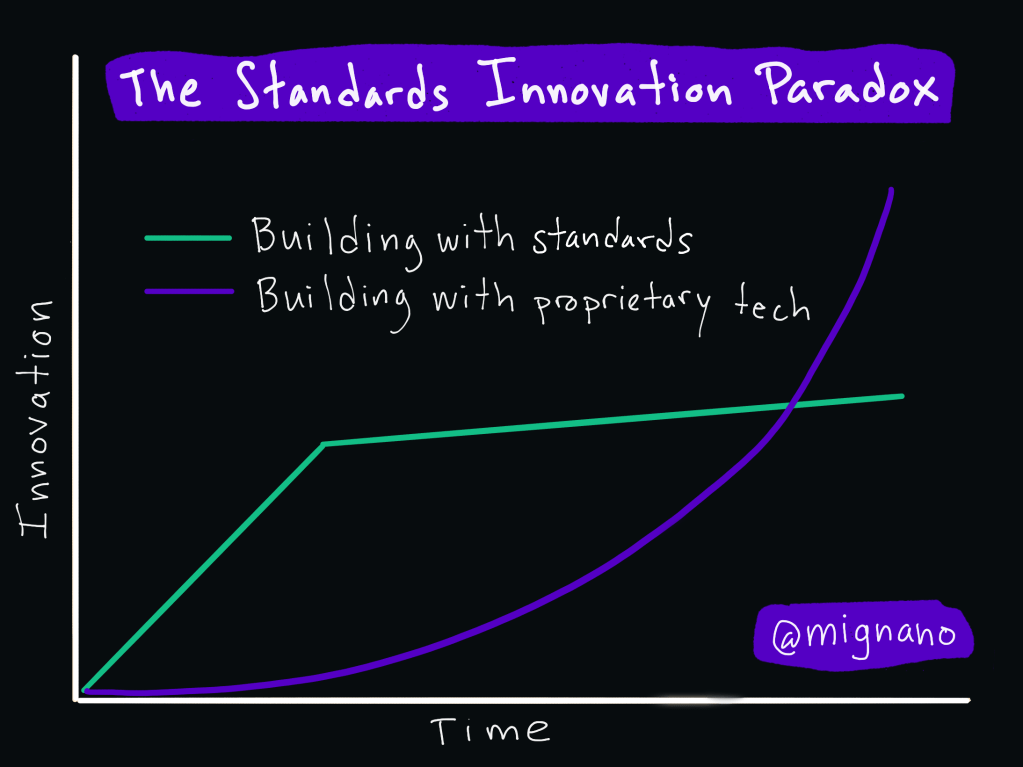

Few tactics are as potent a weapon against incumbents as gaining adoption of a new, proprietary format. As I wrote about in The Standards Innovation Paradox, when new formats succeed, they provide startups with a huge competitive advantage. If a new team’s product outputs a unique, proprietary format that reaches scale, the startup becomes much more defensible than a product that operates with a standardized format (such as a standard image or video file). This is because the cost to others of adopting the new format for an existing product often requires reworking infrastructure, user experience, or even an entire business model.

Snapchat

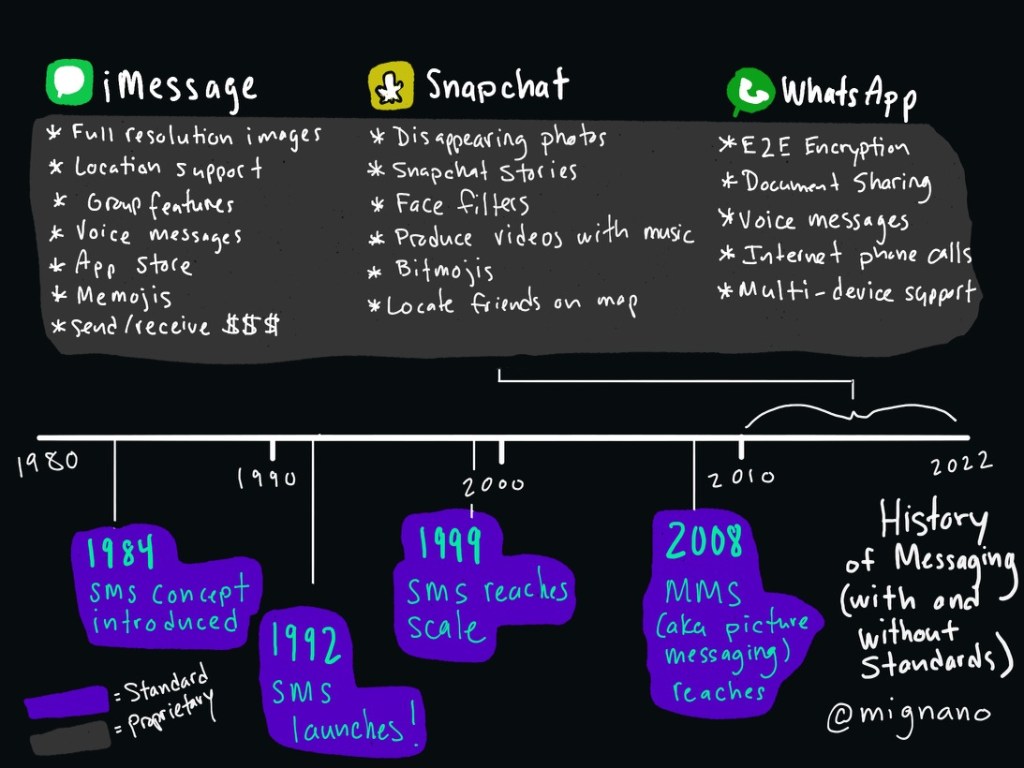

There’s perhaps no better example than Snapchat’s introduction of their signature “snap” format to illustrate the point. Prior to Snapchat, the most common form of sharing on platforms like Instagram and Facebook was through basic image files. These products (and many others) were perfectly designed to support the static, non-dynamic nature of a standard photo format. But Snapchat’s signature “snap” format offered a new way to share moments (in the form of photos or short videos) which would then disappear after a specific amount of time, rather than live on in perpetuity on recipients’ devices. This unique format offered a fun and more spontaneous way of sharing that went far beyond a static photo that lived on forever. Users could create and share moments throughout their days without worrying about the permanence associated with legacy image formats. This made users feel less pressure to share more than on other platforms, which drove Snapchat’s engagement to the moon.

Snap then doubled down by introducing another unique format: stories. Launched in October of 2013, stories offered a new way to share multiple snaps together as a creative narrative, encouraging users to create even more content.

Eventually, after seeing the success of Snapchat’s unique formats, incumbents like Instagram and Facebook eventually raced to introduce their own versions of snaps and stories, but the challenger platform had already gained a substantial first-mover advantage, which helped propel it to the scale of a massive, publicly traded company worth tens of billions of dollars.

The strategy worked: while Snapchat didn’t invent the concept of image or video sharing, the proprietary formats they brought to the world with the snap and stories formats revolutionized social media and made it hard for others to follow without massive investment. By focusing on light-weight, ephemeral, narrative storytelling, Snapchat found a new way to engage users, demonstrating how unique formats can challenge even the biggest players in the market.

AI-First Formats

Now, AI is making it possible to introduce brand new formats that didn’t previously exist. Take generative video avatars, as one example. Previously, to make compelling sales or training videos, users had to capture raw video footage of human beings speaking. As a result, video editing products have adopted a standard mode of editing and production, entrenched in decades of common user experiences. This standard UX is built to support the specific workflows of capturing video, importing it to a timeline, and enabling users to edit these videos. But now, through AI-first products like Synthesia, Veed, Tavus, and HeyGen, videos of people speaking can be generated dynamically. This not only eliminates the need to capture raw video footage from cameras (saving users time and effort), but it means that the entire user experience associated with editing these videos can be reimagined from the ground up to support the new capability more efficiently. In some ways, this new approach invalidates the legacy user experiences of classic video editors, and forces incumbents to deeply rethink their products and businesses to support the emerging avatar use case.

2. Value Destruction

When a new product’s business model threatens to create value destruction for an incumbent, it becomes much more formidable. An example could be as simple as undercutting an incumbent’s prices or offering a service that the incumbent can’t replicate without severely wounding their existing business. And while this is a tried and true strategy for new entrants, it requires a delicate balance. Destroying others’ value can’t be the only tactic pursued; instead, startups must also create value for the customer in ways the incumbent cannot. Otherwise, the incumbent will also lower prices and leverage their massive scale to simply offer a better product.

Robinhood

One recent example of the business model destruction strategy is Robinhood, the company that offers commission-free trades of stocks, ETFs, and cryptocurrencies. Robinhood’s free trading, paired with a highly accessible, easy to use app (adding differentiated value beyond just undercutting prices), made it a no brainer for new traders to adopt. This was a major blow to incumbent brokerage firms, which typically charged fees for every single trade and catered to a more sophisticated type of trader. To compete, these traditional brokerages had to slash their fees, which represented a meaningful chunk of their revenues, effectively causing value destruction to their existing businesses. Many of the products in this market have since followed Robinhood’s lead, but the damage is already done; Robinhood is a publicly traded company worth more than $10B as of this writing.

Airbnb

And Airbnb created a platform that made it easy for people to rent out their homes or spare bedrooms to travelers, thus competing directly with hotels. This model was a game-changer in the hospitality industry and was a classic case of value destruction. Traditional hotels, bound by fixed costs and regulatory norms, found it difficult to compete without making substantial changes to their operational model. Value destruction…check.

AI-Inflicted Damage

AI makes it easier for certain types of startups to inflict swift and aggressive damage to incumbent business models. Take legal services, as one example. While there have been recent headlines around how AI-powered legal services have stumbled in the actual courts, it’s clear the technology has potential to be very disruptive for the category (or least leveraged as an efficiency driver). Think about it: Huge law firms charge exorbitant fees to fund (and profit from) the sheer human-power of their legal partners and associates. The skills of these highly educated lawyers is worth a lot, thus creating a large market for the best law firms in the world. But like highly skilled lawyers, new large language models have also proven to be effective at reading, analyzing, and even writing vast amounts of text. Startups like EvenUp are leveraging AI for specific legal services for a fraction of what they would typically cost. And law firms can’t simply turn around and use AI instead of people; this would make it impossible for them to justify the high costs of their lawyers, thus severely disrupting their business model. It’s a classic case of value destruction, all powered by AI.

3. Hidden Data Moats

In the world of AI, the concept of a “data moat” refers to the advantage a company gains through its access to (and usage of) high-quality, differentiated data. In essence, the more unique data an AI product can learn from, the more effective it becomes. For AI startups, developing a data moat involves amassing unique, valuable data that isn’t easily accessible to others, and using it to train their own AI models. And once a startup has built a substantial data moat, it becomes extremely difficult for other companies (including incumbents) to catch up, unless they too can access the same volume or quality of unique data to train their AI systems. But once the moat forms and strengthens, it can be really hard for others to catch up.

So how can a startup that’s starting from zero build a data moat? There are a few potential paths, such as collecting data through their own unique services or doing partnerships with other companies that have unique datasets. Just keep in mind that incumbents can also do these things, so startups have to find a way to access a hidden moat not easily accessible by others.

Palantir

There are a few classic, recent examples of data moats. Palantir, as one example, built an initial moat through its work with the United States government. The company’s early product was built for the intelligence community and focused on assisting in work on counterterrorism. This involved processing vast amounts of data from hard to reach sources, such as reports from agents in the field, intercepted transmissions, and private bank transactions. But over time, as the company expanded its customer base beyond the government to include financial institutions, healthcare providers, and other industries, Palantir continued to strengthen its moat by integrating and analyzing their diverse, massive datasets. By amassing such a vast and unique dataset, Palantir created a competitive moat that has made it hard for other companies to compete to this day.

TikTok

A well known, more recent example of a data moat is the TikTok algorithm. TikTok has amassed a treasure trove of highly entertaining, short form video content. But more than that, they’ve found a way to tune the TikTok user experience such that everyone using it is matched with highly personalized and relevant content each and every time they use the product, all through a unique data moat. The result is a platform that’s so effective, it has forced all of its competitors to change the way they distribute content, which I wrote about in The End of Social Media. So how do they do it? TikTok dissects users’ behavior upon each and every viewing of a video, including tracking their duration of consumption and analyzing interactions with the user interface. It’s even rumored that they monitor facial expressions of users as they watch videos through smartphones’ front-facing cameras. The result is a nearly impenetrable data moat that both gets stronger – while also improving the product experience – every time someone uses the product.

AI-Propelled Moats

Perhaps it’s obvious, but data moats are by definition, baked into AI products. Providers of large language models, such as OpenAI, leverage their own massive data moats to ensure their models are the best. However, there are ways for startups to build their own moats by offering AI in new and unique experiences, thus in turn generating a new data moat. For example, recent chatbot platforms like Circle Labs, Character.ai, and Replika are using AI as the foundation of their experiences; specifically, users of these products chat directly with characters that are powered by AI. As conversations with these AI-characters go on, the data powering the characters becomes better, thus making the conversations higher quality, driving even more conversation. It’s a classic flywheel of improving engagement while strengthening a data moat, all propelled by AI.

The Twist: AI startups are just startups

Startups which want to fend off looming incumbents’ distribution advantages must attempt to make their businesses as defensible as possible. This requires being nimble, tactical, and leveraging as many strategic advantages as possible. And while unique formats, value destruction, and data moats can all help, there are many other tactics to be pursued, as well.

But here’s the thing about the above three tactics: they are not at all unique to AI startups. In fact, if you went back and re-read this entire essay but skipped all of the AI-specific sections and examples, the tactics would still hold true for all startups.

What does this all mean? It means that if you’re building an AI product – despite now being able to leverage an awesome, transformative technology – it’s really no different than building a non-AI product. AI can help your startup do magical things it simply couldn’t do previously, and the ways in which this is motivating teams to offer truly novel experiences is inspiring; however, in this context, AI is similar to the other tools your products can leverage, like cloud computing, mobile app development, live audio/video streaming, GPS, web3 . . . the list goes on and on.

At the end of the day, finding success for your product is not about leveraging the latest and greatest technology just because you can; it’s about building and shipping products that solve real problems for real people, and scaling those really f*cking fast once they find product market fit. After all, that’s what the incumbents did when they were startups, too. If your team can do that, you’ll walk away from the application layer battlefield victorious.

—

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this, I hope you’ll consider sharing it with a friend.

Want to share your AI-first product with me? Shoot me an email.

Want to read more of my product strategy essays? Follow/subscribe on Substack, X, and LinkedIn.